Casey Walsh

Historical Fiction

May I Recommend ...

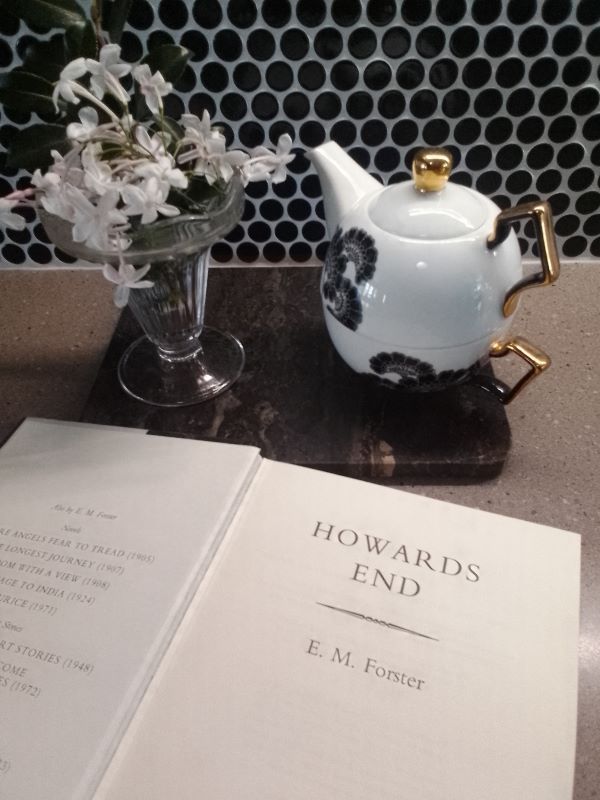

Don't you just love the serendipitous journeys we take as book lovers? My research into the setting of my next novella (early 20th century pre-WW1) brought me to the Australian classic, Picnic at Hanging Rock, which then led me to read two biographies of the author, Joan Lindsay. She was influenced by E.M. Forster and Henry James. I'd never read Forster, so I picked up Howards End as I loved the movie adaptation of this seminal work, especially the 1992 Merchant Ivory production which is faithful to novel.

In awe of Forster's gentle lyricism, I found myself memorising page numbers where some especially sublime passage was found so I could return to savour it again. He painted such dreamy landscapes, layered with emotion and memory and consequence, inextricably linking the fate of people with places. It is a book about entwined destinies and the ripples of cause and effect, much like Hanging Rock.

So if you find yourself at a loose end of an evening, why not let yourself be transported back to the brighter, gentler Edwardian era with one or both of these classics? Then, treat yourself and watch the movies!

Letters, real and imagined ...

In another happy coincidence, I just finished devouring Miss Austen, a gorgeous BBC drama which portrays a few weeks in the life of Jane Austen's elder sister, Cassandra, years after the author's death and just before she burns Jane's letters (she did actually burn them, much to the horror of every Austenite). The mini-series imagines what was in those letters, revealing the secrets, scandals and tragedies of the extended Austen family. It is an achingly beautiful portrayal of enduring sisterly love and the fierce loyalty Jane and Cassandra had for each other.

Then I read A Room Made of Leaves by national treasure, Kate Grenville. It's a fictional memoir based on the actual letters of Elizabeth Macarthur, wife of the prominent colonial-era politician and celebrated pioneer of the Merino sheep industry of Australia. The supposed memoir is discoverd 150 years after her death, revealing the astonishing interior life of a woman who was more than a match for her firebrand husband. The novel explores the danger of false stories concealing real ones - very much a 21st century dilemma.

What impressed me with both of these works was the ingenious grafting of richly imagined, fully-fleshed out branches of stories with their wonderfully complicated and conflicted heroines, onto mere saplings of fact. Does it matter if those letters or the memoir never existed, or if they did, that we can never know the sentiments they contained? No, and that is testament to the power of brilliantly-conceived, superbly-written fiction to suspend disbelief.

Life imitates art ...

Murder by Mushroom.

Recently, a verdict was given in the so-called mushroom murder trial in the Australian town of Morwell. A woman was charged with the murder of three of her ex-husband's relatives and the attempted murder of a fourth, after serving them a lunch of beef Wellingtons laced with death cap mushrooms.

The case, like something out of a Miss Marple novel, captured the attention of the world's new outlets and the fascination of true crime enthusiasts, tourists and podcasters, who swarmed over the country town for the duration of the trial.

Amid the morbid curiosity for the sensational details of the case and endless speculation about the murderer's motives, the victims can easily be forgotten. As one of the investigating officers reminded the public, three people died slow and painful deaths and a community is still mourning their passing.

This sobering comment reminded me of one of my all-time favourite crime novels: The Documents in the Case by Dorothy L. Sayers. For those of you who have never heard of Ms Sayers, she was a contemporary of Agatha Christie and is best known for the Peter Wimsey detective series. This book doesn't feature her most famous sleuth but I would still recommend it to lovers of classic golden age mysteries. Poisonous mushrooms, unreliable narrators and Ms Sayers' trademark wit and appreciation for the ridiculous feature heavily.

Rediscovered treasure ...

The Sow's Ear by Bernard Cronin (published 1933) is a rural drama and love story set in late 19th and early 20th century Tasmania, Australia.

June, a sensitive young dreamer, is oppressed by her zealot father and the suffocating expectations of her small community, among whom, ‘love had no enchantment, no visioning, no avian flight. It was stupid and conventional, a mere bodily functioning’. She is promised in marriage to a much older man from whom she instinctively recoils. Her grey life of drudgery and fear is gradually filled with light and hope as she develops a friendship with the town’s new teacher, Brian, a genteel young man from the city who fosters her love of books, poetry and nature. But just as their mutual passion finds expression, tragedy strikes.

The book is divided into three parts, ‘Morning’, ‘Noon’ and ‘Night’ and in the last part we find June at age thirty, now a wife and mother of three, eking a living on a subsistence farm, all her girlhood dreams obliterated. A series of disasters shreds the last of her courage and brings her to the verge of despair when suddenly there is a glimmer of hope from an unlikely source.

This is literary fiction in the tradition of Thomas Hardy and Henry James. Sadly, it’s out of print, but I wish it weren’t so that a new generation of readers could appreciate its exquisite poignancy and gorgeous poetic depictions of the land and sea. I read it when I was a teenager and it stayed with me until I found it again twenty years later. It made me cry all over again.